In April 2006 I visited a town called Waveland in Mississippi, to assist in the ongoing cleanup operation after hurricane Katrina all but wiped the small Gulf Coast town off the map back in August 2005. Now 15 months later I’ve returned to Waveland to see the area that resembled a war-zone last time I was here.

The scale of destruction caused by hurricane Katrina is almost impossible to comprehend. We’ve all seen the television footage and dramatic pictures from New Orleans and other Katrina hit areas, but as arresting as they might be nothing can quite prepare you for the experience of seeing the devastation first hand.

Nearly two years after Katrina hit you might assume that America, the richest nation on earth, would have fixed everything that the storm smashed. This is after all a country that is capable of spending more than two hundred million dollars a day on a seemingly endless war in a far off land. Surely then, cleaning up after a hurricane would be a breeze.

Of course, the issue isn’t that simple. There are various factors that complicate the process of rebuilding. The promised $85 billion of Federal aid has been slow to trickle through to all those who need it, and there are still many claims that not enough is being done on federal and state levels.

Much of the destruction affected private property which lead to the insurance industry struggling to settle the $34.4 billion of claims. But as high as the figure for insured losses may be it pales when compared with the $125 billion figure for total economic losses of hurricane Katrina estimated by Risk Management Solutions, a risk modeling agency from Newark, California.

The majority of those worst affected by Katrina suffered from flood damage caused either by a failure of the levies in New Orleans, or by huge 35 foot storm surge waves that crashed into coastal towns like Waveland. However, insurance companies have rejected many claims made after hurricane Katrina based upon the understanding that private insurance companies do not cover flood damage, no matter if that flood was a direct result of a hurricane weather system. This assertion by private insurance companies has left many people in quite awful financial situations, often paying mortgages on houses that simply no longer exist, and lawsuits against insurance companies look unlikely to succeed.

“Unfortunately many people choose not to buy flood insurance even though it can be immensely invaluable. The policies under the National Flood Insurance Program will pay up to $250,000 for residential buildings plus another $100,000 for contents. The average premium is around $400 a year for $100,000 worth of coverage.” Said Carolyn Gorman, vice president of the Insurance Information Institute.

“If you live in a flood plane your bank will require you to have flood insurance when you get your mortgage. Unfortunately many people let that policy lapse, leaving them uncovered when a disaster occurs. If your home is totally destroyed and you can’t make your mortgage payments on a home that no longer exists, then your bank will probably foreclose.”

As an outsider looking in on this situation it’s perhaps too easy for me to make sweeping judgments about who I think isn’t doing enough, and what more needs to be done. But I have to temper my disappointment at seeing the many FEMA trailers parked in neighborhoods that have simply vanished, with the fact that there are a great many people actively working to assist in the the recovery of this region.

Leaving the trailers behind

Leaving the trailers behind

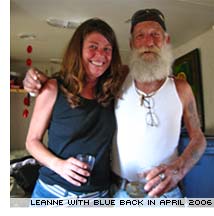

In her rickety FEMA supplied trailer on the plot of what used to be her home, I spoke once more with Leanne, whom I had met last year. “This is a new trailer,” She told me as we sat at her dinner table. “It’s bigger than the last one.”

Last time I was here Leanne smiled for a picture in her tiny trailer with her friend ‘Blue’ who has since passed away. I’ve often thought about Leanne and wondered how she was doing. I doubt I’ll forget the tour of her house that she gave us last year. Katrina had completely destroyed her home leaving just the flooring as evidence of the house that once stood. “This is the kitchen.” She said, while stood not far from a smashed car, snapped trees, and a painted sign that read ‘Rosey, Rest in Peace.’

Leanne is soon to be rehoused in a Katrina Cottage, a low cost housing unit created to help replace the 65,000-plus Mississippi homes lost to the hurricane. Designed in the style of a downscaled Mississippi-style coastal cottage, the 308 square foot properties come complete with a porch and oversized windows to give the property an airy spacious feel. They’ve already proved very popular not only in Katrina hit areas but across the country with developers considering the design for high-end beach communities on other coasts.

Leanne is excited at the prospect of moving out of her FEMA trailer at long last, though it will be a bitter sweet moment as she will no longer be on the plot of her former home just a block away from the beach.

In my collection of photographs shown here I wanted to try and find comparisons of the same locations taken first 6 months after the storm, then again at this time, nearly 2 years after the storm. The difficulty is that actually identifying locations is almost impossible given the lack of recognizable landmarks. Even locals struggle to identify photographs of areas that at one time might have been instantly recognisable.

A very obvious difference is the $267 million reconstruction of the two-mile highway 90 bridge that now stands 85 feet high at its tallest spot as it connects Bay St. Louis to Pass Christian.

Opened amid a rousing celebration in May 2007, the bridge is seen by many as an essential lifeline and a symbol of resilient progress. Bay St. Louis Mayor, Eddie Favre, hailed the bridge a tremendous psychological and emotional boost.

“People saw it as an absolute necessity.” He said. “For 626 days, we felt that isolation. The bridge, in so many ways, whether it was walking or fishing, was just so much a part of our daily life.”

Bobbie’s house

In the days that followed Katrina various internet bulletin boards were swamped with messages from people anxious to find information of family and friends. “I am desperately seeking Rachael Fleuriet from Waveland and Bobbie Durkovich from Bay St.Louis.” Read a message from Dandy Blethroad posted in a comment on the weather.com blog.

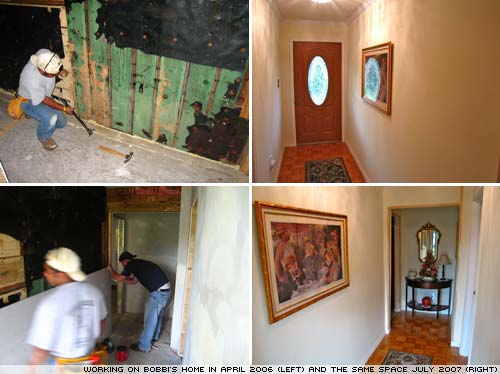

Some sixth months later myself and two other volunteers were at the home of Bobbie Durkovich putting up dry wall. She was a smiling good humored lady who fueled us with ice cold cokes as we worked in her flood damaged house.

I was keen to see Bobbie again on my return to the area. When we left Bobbie back in April she hugged all three of us and cried as she thanked us and told us how proud our parents should be. Amid the wreckage of Katrina much of what we did felt somewhat deflating due to the fact there was simply so much more that needed to be done. But with Bobbie’s house, despite wanting to stay there until the job was finished, we could at least see very real signs of progress, progress that other volunteers would continue.

I was keen to see Bobbie again on my return to the area. When we left Bobbie back in April she hugged all three of us and cried as she thanked us and told us how proud our parents should be. Amid the wreckage of Katrina much of what we did felt somewhat deflating due to the fact there was simply so much more that needed to be done. But with Bobbie’s house, despite wanting to stay there until the job was finished, we could at least see very real signs of progress, progress that other volunteers would continue.

Bobbie greeted me with a broad smile and a heartfelt hug. “Come on in.” She said, proudly showing me her completed kitchen along the way. I was pleased to see her in what was once again a homely space. She showed me the hallway by her front door where fellow volunteer, Keith, had turned the air blue with his colorful language as we put up the dry wall. I’d never done any kind of building work before, and I had no idea what one of my tasks, ‘mudding’, actually entailed. These were new skills I learned in Bobbie’s house, and as she showed me the various rooms we had worked on I joked with her that my ‘mudding’ effort looked better than I imagined it might.

This is our home

Looking at these pictures and remembering that these photographs are taken nearly 2 years after hurricane Katrina struck, one might find themselves wondering why anyone would choose to rebuild and live in an area where the risk of this kind of destruction were a possibility.

My friend Susan Stevens, a Waveland resident whom I met while volunteering in 2006, answers that question. “We return and rebuild because this is our home.” She writes in her own Katrina story.

“We have friends here that have known us all our lives. Our families are here. Our memories are here. We have spirit and commitment and this is our home. What we lost was ‘stuff’. What we have gained cannot be measured by words.” Put in those terms it’s easy to relate to how important the idea of ‘home’ actually is.

There’s still a long way to go for the residents of Gulf Coast. The challenges of rebuilding homes, and returning the communities and neighborhoods to something nearing their pre-Katrina state is a monumental task.

I never saw the Mississippi Gulf Coast before Katrina, but the few pictures I’ve seen leave me hoping that this area manages to stave off the advances of high rise condo developers who will surely seek to snap up and develop land next to the sun soaked beaches. Such developments could bring tourists and money but at the same time would very likely steal the small town charm that makes places like Waveland feel like home, or at least what we would all like home to feel like.

—

A town called Waveland

Hurricane Katrina

Hurricane Katrina stories website

Rising from ruin : MSNBC Katrina special

US coast guard : Before and after Katrina photography

A Bridge Restores a Lifeline to a Battered Town

‘Katrina Cottages’ : Home after a FEMA trailer

‘Katrina Cottages’ prove popular

Buy a ‘Katrina Cottage’

Hurricane Katrina stats

[Map] pPre-Katrina Waveland Sattalite view

[Video] My video shot 6 months after Katrina

[Video] Christ Church Bay St. Louis

[Video] Katrina Insurance Claims Hearing: Rep. Taylor Testimony

[Video] Katrina Stories: Johnny, Bay St. Louis

[Video] CNN Presents : Bay St. Louis – The town that fought back (Part 1)

[Video] CNN Presents : Bay St. Louis – The town that fought back (Parts 2,3,4,5, and 6)

Wrote the following comment on Aug 9, 2007 at 1:08 am

That’s the bridge my sister’s brother-in-law was an engineer for.

Wrote the following comment on Aug 11, 2007 at 2:07 am

many things can be said on all of this; i walk away from each one of your posts with an amazing awareness of your talent. thanks for sharing.

Wrote the following comment on Aug 11, 2007 at 5:10 am

Simon, I read this out loud to George and the pictures and the story were amazing. My roommate from college lived through this in Slidell, but a year later her husband of over 20 years asked for a divorce. We had a single Mom and her son live with us from New Orleans for a couple of months and they’ve moved back to Baton Rouge now. Life goes on, but it will always never be the same again. Thanks for sharing!

Wrote the following comment on Aug 11, 2007 at 11:37 pm

This was a great read…but more importantly for me, a resident of Alabama (and also from Florida when Andrew came through); it’s wonderful to know that people from all over the world were coming to help. It makes all the difference.

Wrote the following comment on Aug 12, 2007 at 2:02 am

great pictures.. the before and after ones i like the best- great reference point.

Wrote the following comment on Aug 14, 2007 at 12:25 am

good stuff mate. you should approach newspapers and publishers with your website… you could have a career in writing….

Wrote the following comment on Aug 17, 2007 at 3:23 am

Thank you for the compliments everyone! I’ll pass them right back to the folks I met though. Had I not met these ordinary people who became amazing because of the situation they found themselves in, I would not have been able to share their amazing stories with you.

Wrote the following comment on Nov 5, 2007 at 11:06 pm

I see that you are looking for Rachel F. So are alot of other people that she has ripped off with insurance money.Being one of her lease to own tenents and loosing all of my paper work to Katrina I have no evidence proving that I have been paying her for 9 years and not collect a dime from the ins.co. As I said earlier there are several other people that she has done this to and I think people should beware of her and her scams. Without saying I cannot afford a lawyer much less housing.Thank you for letting me express my sorrow.